Long before Portuguese explorers set foot on South American shores, the name “Brasil” already graced European maps as a mythical Irish island Brazil floating mysteriously in the Atlantic Ocean. This phantom landmass, known variously as Hy-Brasil, O’Brasil, or simply Brasil, appeared on nautical charts for over five centuries, challenging our understanding of medieval cartography and sparking fascinating debates about the origins of geographical names. The existence of this legendary isle on Brazil island pre-1500 maps presents one of history’s most intriguing chronological puzzles: how did an Irish mythical island share its name with the South American nation discovered 175 years later?

This extraordinary coincidence has captivated historians, cartographers, and etymologists for generations, raising profound questions about the interconnectedness of medieval geographical knowledge and the mysterious ways in which names traverse cultures and centuries. The Hy-Brasil legend represents far more than mere cartographic curiosity; it embodies the collision between Irish folklore, Mediterranean mapmaking traditions, and the relentless human quest to chart the unknown.

The legend of Hy-Brasil: origins and characteristics

Celtic roots and mythological foundation

The mythical Irish island of Brasil emerges from the rich tapestry of Celtic mythology, where it occupied a sacred place alongside other supernatural realms of the Otherworld. According to Irish folklore, this ethereal landmass was cloaked in perpetual mist, revealing itself to mortal eyes only once every seven years, when atmospheric conditions aligned in mystical harmony. The island’s name derives from ancient Irish sources, with scholars proposing two primary etymological pathways: “Uí Breasail,” meaning “descendants of Bresail” (referring to an ancient Irish clan), or the Old Irish “í bres,” translating to “island of beauty” or “island of worth.”

The characteristics attributed to Hy-Brasil mirror the archetypal paradise found throughout Celtic tradition, particularly the concept of Tír na nÓg (Land of the Young). Medieval Irish texts describe it as a realm where time flows differently, where inhabitants enjoy eternal youth and perfect health, and where sorrow and death hold no dominion. This otherworldly paradise was said to be home to an advanced civilisation possessing knowledge far beyond that of medieval Europe, with some accounts describing magnificent cities, abundant treasures, and magical properties that defied natural law.

Gerald Griffin’s evocative 19th-century poem captures the island’s mystique perfectly:

“On the ocean that hollows the rocks where ye dwell,

A shadowy land has appeared, as they tell;

Men thought it a region of sunshine and rest,

And they called it Hy-Brasail, the isle of the blest.”

These literary depictions reinforced the island’s status in Irish cultural consciousness as more than mere geographical speculation, but as a symbol of hope and transcendence.

Recurring motifs and symbolism

The Irish mythical islands tradition encompasses several recurring themes that distinguish Hy-Brasil from ordinary geographical features. Contemporary accounts consistently describe the island as perfectly circular, often bisected by a central river or channel running east to west. This distinctive morphology appeared with remarkable consistency across different cartographic traditions, suggesting either a shared source or deeply embedded symbolic meaning.

The island’s inhabitants were frequently portrayed as beings of exceptional wisdom and benevolence, greeting occasional visitors with gifts of gold and silver. Captain John Nisbet’s 17th-century account, while likely apocryphal, exemplifies these themes by describing an encounter with a solitary sage living in a stone castle, surrounded by large black rabbits—details that echo broader Celtic motifs of wisdom, magic, and the boundary between human and animal realms.

Cartographic appearances: Brasil on pre-1500 maps

Early Mediterranean cartography

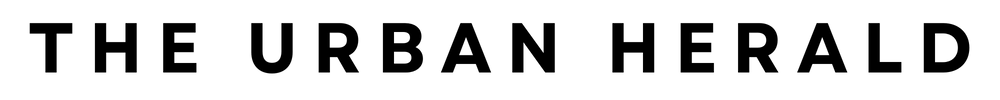

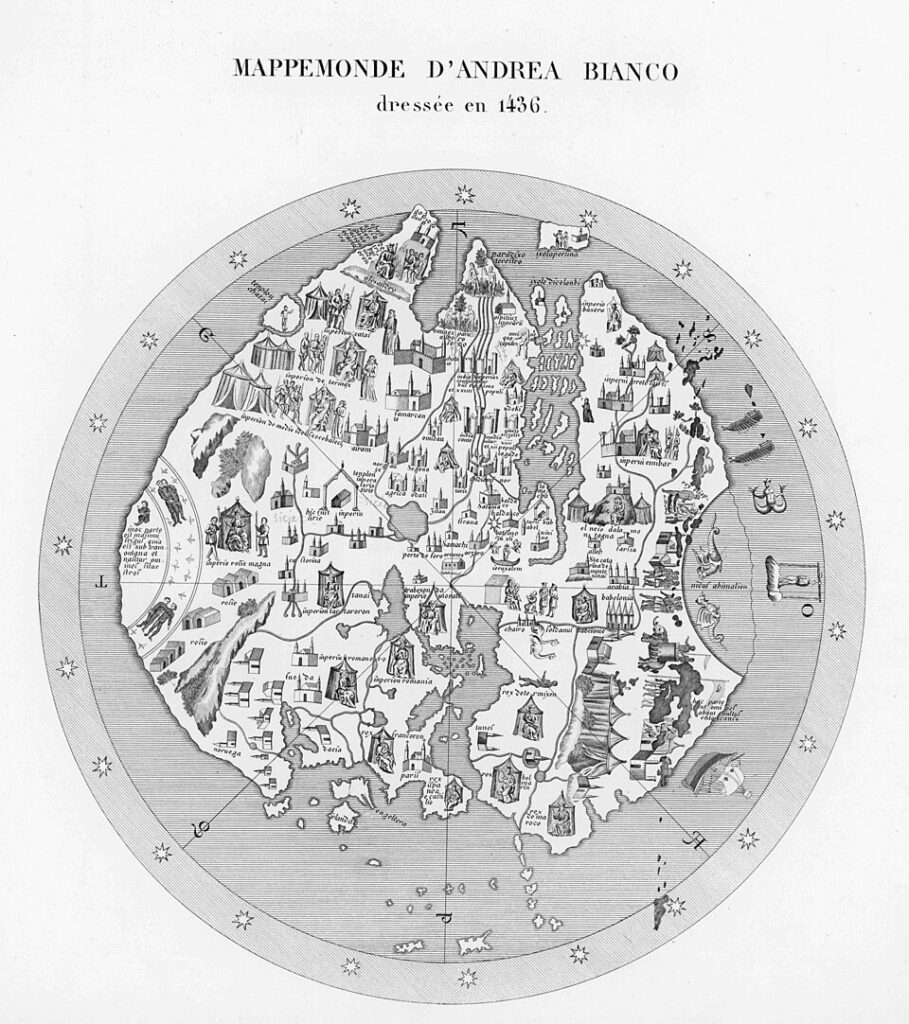

The first documented appearance of the mythical Irish island Brazil occurs on Angelino Dulcert’s portolan chart of 1325, where it appears as “Insula de Brazile” positioned west of Ireland. This Majorcan cartographer, possibly of Genoese origin, established a cartographic tradition that would persist for over five centuries. Dulcert’s innovation represents a pivotal moment in the cartographic history mythical islands, marking the transition from purely oral tradition to documented geographical speculation.

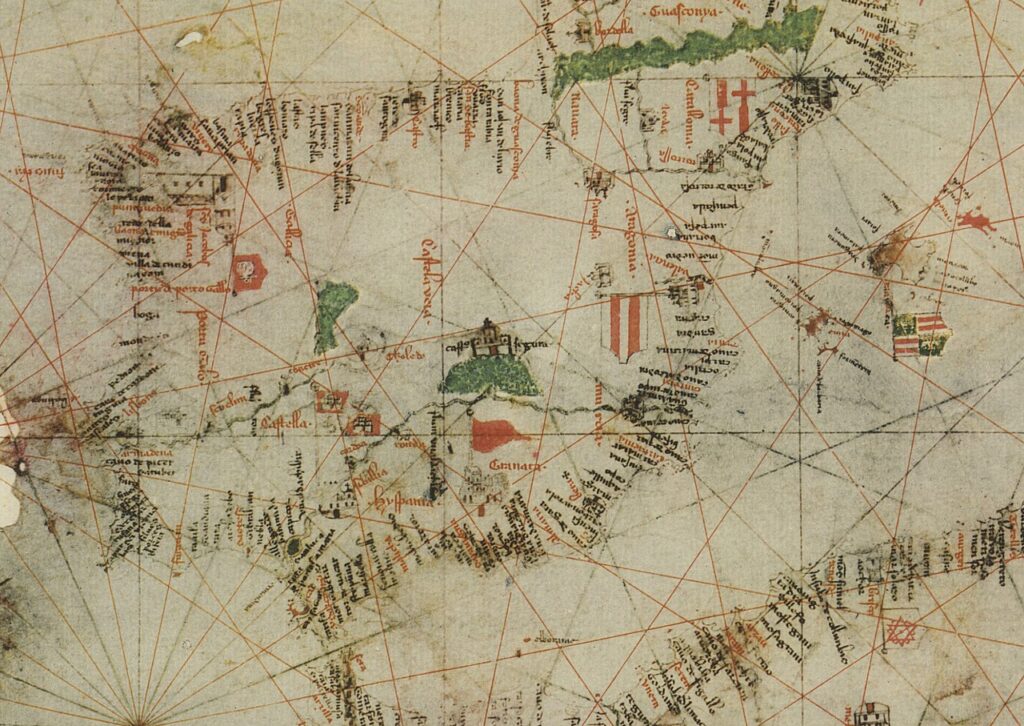

The Venetian navigator Andrea Bianco further refined this cartographic legacy with his 1436 atlas, marking the island as “Insula de Brasil” within a comprehensive maritime collection that influenced subsequent mapmaking across Europe. Bianco’s work, created during the height of Venetian maritime power, demonstrates how Brazil island pre-1500 maps reflected not just geographical knowledge but also commercial interests and navigational requirements.

The Catalan Atlas and peak representation

The 1375 Catalan Atlas, attributed to Jewish cartographer Cresques Abraham, provides perhaps the most famous depiction of the legendary island. This masterwork of medieval cartography shows “Ylla de brasil” positioned strategically in the Atlantic, demonstrating the sophisticated geographical understanding of 14th-century Majorcan mapmakers. The atlas represents the culmination of Mediterranean cartographic achievement, incorporating the latest knowledge from across the known world whilst preserving mythological elements that reflected contemporary worldviews.

The consistency of Brasil’s placement across different cartographic traditions suggests either remarkable coordination among medieval mapmakers or the influence of a common, now-lost source. Portuguese cartographer João Teixeira Albernaz’s 1630 chart continues this tradition, depicting “Do brasil” as a circular island bisected by a central waterway. These ancient maps island of Brazil reveal evolving cartographic techniques whilst maintaining core mythological elements.

Geographical variations and naming conventions

The island’s position varied considerably across different maps, appearing at various locations from the coast of Ireland to positions near Brittany, the Azores, and even Newfoundland. This geographical flexibility suggests that Brasil functioned less as a specific location than as a conceptual placeholder for unknown or mysterious lands. Medieval cartographers employed at least thirteen different spellings for the island’s name, including “Bracile,” “Brazyl,” “O’Brasil,” and “Hy-Breasail,” reflecting regional linguistic variations and evolving orthographic standards.

The persistence of Brasil on maps despite repeated failed expeditions demonstrates the powerful influence of cartographic tradition over empirical evidence. Even as late as 1753, British cartographer Thomas Jefferys marked the location as “Imaginary Isle of O Brazil,” acknowledging its fictional status whilst maintaining its traditional position. The island’s final cartographic appearance occurred on British Admiralty charts in 1873, listed as “Brasil Rock,” marking the end of a 548-year cartographic legacy.

The name “Brasil”: a pre-Columbian puzzle

Etymology of the mythical island

The Brazil island name origin presents one of medieval cartography’s most enduring mysteries, with linguistic evidence pointing toward multiple possible sources. The primary theory connects the name to Irish Gaelic “Uí Breasail,” referencing the descendants of Bresail, a legendary figure associated with ancient Irish kingship and otherworldly realms. Alternative etymological investigations propose derivation from Old Irish “í bres,” combining “í” (island) with “bres” (beauty, worth, or greatness), creating a toponym meaning “beautiful island” or “island of worth.”

Medieval Latin sources suggest another fascinating possibility: connection to “brasilium,” referring to a red dye derived from certain trees and known throughout medieval Europe as a valuable trading commodity. This interpretation gains credibility from Italian geographer Paolo Revelli’s research, which identifies brasil-dye as a significant factor in medieval cartographic nomenclature. The widespread appearance of “brasil” as a locational marker for dye sources throughout medieval maps supports this commercial interpretation.

However, the pre-Columbian map anomalies represented by Brasil’s consistent appearance suggest deeper cultural and linguistic currents at work. The chronological precedence of the Irish island’s name—appearing 175 years before South American contact—establishes an unambiguous temporal framework that challenges simple etymological explanations.

Chronological precedence and historical significance

The temporal gap between the mythical island’s first cartographic appearance (1325) and the Portuguese discovery of South America (1500) creates a fascinating historical puzzle that has implications far beyond mere nomenclature. This 175-year precedence establishes the Irish Brasil as the elder claimant to the name, fundamentally altering our understanding of how geographical names develop and spread across cultures.

Roger Casement’s early 20th-century lecture, delivered during his diplomatic service in Brazil, articulated one of the most compelling arguments for Irish etymological priority. Casement proposed that the name Brasil could only have originated from Celtic legendary traditions associated with the “islands of the blessed” and the Irish concept of Tír na nÓg. His argument gains strength from the documented presence of Irish maritime knowledge in medieval European trading networks.

The persistence of Brasil on maps throughout the medieval period, despite numerous failed expeditions, demonstrates the remarkable power of mythological thinking in shaping geographical understanding. Expeditions from Bristol in 1480 and 1481 specifically sought “the Isle of Brasile,” indicating that the name had achieved sufficient recognition to justify costly maritime ventures. John Cabot’s 1497 voyage may have been influenced by prior Bristol expeditions that claimed to have found “Brasil,” though historical evidence remains inconclusive.

The Brasil etymology debate: chronological evidence and scholarly analysis

Timeline of name appearances

Mythical island Brasil

- 1325: First recorded as “Insula de Brazile” on Angelino Dulcert’s portolan chart

- Etymology: Celtic/Irish “Uí Breasail” (descendants of Bresail) or Old Irish “í bres” (island of beauty/worth)

- Alternative theory: From Medieval Latin “brasilium” (red dye-wood), referencing ember-like colour

South American Brazil

- 1500: Initially named “Ilha de Vera Cruz” by Pedro Álvares Cabral

- c.1510: Renamed “Terra de Santa Cruz”

- 1550s: Began being called “terra de brasil” due to brazilwood exploitation

- Etymology: Portuguese “pau-brasil” from “brasa” (ember) + “-il” suffix, referring to red dye

Key chronological discrepancy

175 years separate the first cartographic appearance of the mythical island (1325) from the discovery of South America (1500). This temporal gap is the foundation of the historical debate.

Scholarly positions

Coincidence theory (mainstream)

- Two completely independent etymologies

- No historical connection between names

- Supported by linguistic evidence showing different roots

Influence theory (minority)

- Suggests subconscious cartographic/exploratory influence

- Proposes ‘lexical echo’ phenomenon

- Lacks concrete historical evidence

Pre-Columbian knowledge theory (speculative)

- Most controversial position

- Suggests early European awareness of western lands

- Heavily disputed by mainstream historians

Evidence assessment

Supporting Coincidence:

- Clear linguistic distinction between Celtic and Latin roots

- No documented historical connections

- Different geographical contexts

Supporting Influence:

- Extensive maritime knowledge sharing among European ports

- Common usage of existing toponyms for new discoveries

- Bristol expeditions seeking Brasil before Cabot

Conclusion: Current scholarly consensus favours independent etymologies while acknowledging the fascinating chronological precedence as a historical curiosity rather than evidence of connection.

The Brazilian connection: a coincidence or something more?

The pau-brasil explanation and South American etymology

The accepted explanation for South America’s Brazil name origin centres on the brazilwood tree (Caesalpinia echinata), known in Portuguese as pau-brasil. This tree yielded a highly valued red dye that became the colony’s first major export, leading to the territorial designation “terra de brasil” (land of brazilwood) by the 1550s. The Portuguese term “pau-brasil” derives from “pau” (wood) and “brasa” (ember), referencing the vivid red colour extracted from the tree’s heartwood.

Pedro Álvares Cabral initially named the territory “Ilha de Vera Cruz” (Island of the True Cross) in 1500, followed by the official designation “Terra de Santa Cruz” (Land of the Holy Cross). However, commercial interests gradually overwhelmed religious nomenclature as brazilwood exports gained economic significance. The evolution from sacred naming to commercial terminology reflects broader patterns in colonial nomenclature, where economic value often determined lasting geographical names.

The pau-Brasil vs. mythical Brasil comparison reveals fascinating parallels in colour symbolism, with both names potentially referencing reddish hues—the dye from brazilwood trees and the ember-like qualities associated with the mythical island’s name. However, these similarities may represent convergent etymology rather than historical connection.

Scholarly debates and theoretical frameworks

The debate Brasil name origin encompasses three primary theoretical positions, each with distinct implications for understanding medieval geographical knowledge and cultural transmission. The mainstream coincidence theory posits two completely independent etymological developments, supported by clear linguistic distinctions between Celtic and Latin root systems. This position emphasises the dangers of retrospective pattern-seeking in historical analysis.

The minority influence theory suggests more subtle connections through maritime knowledge networks that connected Irish, Bristol, and Portuguese trading communities. Proponents argue that cartographic and exploratory traditions created “lexical echoes” that influenced naming practices across different geographical contexts. Evidence for this position includes the documented Bristol expeditions seeking Brasil and the extensive maritime connections linking Atlantic European ports.

The most controversial pre-Columbian knowledge theory proposes that some awareness of western lands influenced medieval cartography, potentially explaining the persistence of Brasil on maps despite empirical failure. This position, while lacking concrete historical evidence, draws support from recent archaeological discoveries suggesting more extensive pre-Columbian contact than previously recognised. However, mainstream historians remain deeply sceptical of claims suggesting systematic pre-Columbian knowledge of the Americas.

Modern scientific perspectives and geographical explanations

Contemporary research has identified potential geographical explanations for the Brasil legend, including the Porcupine Bank, a raised area of seabed approximately 200 kilometres west of Ireland. This geological formation, discovered in 1862 by HMS Porcupine, lies 200 metres below current sea level but could theoretically have been exposed during periods of lower sea level. Some researchers propose that folk memories of previously exposed land could have contributed to the Brasil legend.

Optical phenomena provide another scientific framework for understanding Brasil sightings. Superior mirages, caused by temperature inversions over cold ocean water, can create the illusion of floating islands or land masses where none exist. These phenomena, while uncommon in Irish waters, occur regularly in Arctic regions and could explain occasional “sightings” of the mythical island. The 1878 Ballycotton sighting, documented by contemporary observers as a clear island where none should exist, exemplifies how atmospheric conditions can create convincing illusions of land. Such phenomena may have provided periodic “confirmation” of the island’s existence, sustaining the legend across centuries.

Cultural impact and modern legacy

Literary and artistic influences

The Irish mythical islands tradition, particularly the Brasil legend, has profoundly influenced Irish literature, poetry, and contemporary cultural expression. Gerald Griffin’s romantic poem “Hy-Brasil, the Isle of the Blest” established the island as a symbol of unattainable beauty and spiritual longing, themes that resonate throughout Irish literary tradition. The poem’s imagery of a peasant abandoning safety to pursue an illusory paradise reflects broader themes of Irish emigration and the search for better life beyond familiar shores.

Modern Irish musicians and artists continue to draw inspiration from the Brasil legend, with contemporary album projects and documentaries exploring connections between Irish mythology and Latin American history. The persistence of these cultural references demonstrates how Irish folklore lost islands continues to provide metaphorical frameworks for understanding migration, loss, and hope.

The legend’s influence extends beyond Ireland, with scholars like J.R.R. Tolkien acknowledging connections between Brazilian nomenclature and Celtic mythology in his academic work. Barbara Freitag’s comprehensive study “Hy Brasil: The Metamorphosis of an Island” traces the evolution from cartographic error to Celtic cultural symbol, documenting how 19th-century antiquarians transformed Mediterranean cartographic traditions into distinctly Irish mythological narratives.

Contemporary scholarly interest and research

Modern academic interest in the Brasil legend reflects broader scholarly attention to the intersection of mythology, cartography, and cultural identity. The Norman B. Leventhal Map Center’s exhibition “Hy-Brasil: Mapping a Mythical Island” demonstrates continued public fascination with cartographic mysteries and their cultural implications. Such exhibitions highlight how historical myths continue to provide insights into medieval worldviews and the psychology of geographical discovery.

Research into phantom islands has expanded beyond purely historical inquiry to encompass psychological and sociological dimensions of belief systems. The Brasil legend offers a case study in how mythological thinking influences empirical investigation, with implications for understanding contemporary conspiracy theories and belief persistence in the face of contradictory evidence.

The legend’s endurance also reflects deeper questions about the relationship between folklore and geographical knowledge, particularly how oral traditions preserve and transmit information across generations. Contemporary Celtic scholarship increasingly recognises the historical value embedded within mythological narratives, viewing them as repositories of cultural memory rather than mere fantasy.

Conclusion: an enduring cartographic enigma

The story of the mythical Irish island Brazil represents far more than a curious footnote in cartographic history; it embodies the complex interplay between imagination and empirical knowledge that characterised medieval European exploration. From Angelino Dulcert’s first marking of “Insula de Brazile” in 1325 to its final disappearance from British Admiralty charts in 1873, this phantom landmass maintained its position in the Atlantic Ocean for 548 years, outlasting empires and surviving the transition from medieval to modern worldviews.

The chronological precedence of the Irish Brasil name over its South American counterpart raises profound questions about the mechanisms of cultural transmission and the persistence of geographical nomenclature across different historical contexts. Whether the similarity represents pure coincidence, subtle cultural influence, or something more mysterious, the debate Brasil name origin continues to captivate scholars and enthusiasts alike.

Perhaps most significantly, the Brasil legend illustrates how mythological thinking shaped practical endeavours, inspiring real expeditions and influencing actual geographical knowledge. The island’s persistence on authoritative maps despite repeated empirical failure demonstrates the remarkable power of cultural belief systems to resist contradictory evidence. In an age of satellite mapping and digital cartography, the Brasil legend reminds us that our understanding of the world remains fundamentally shaped by the stories we tell ourselves about what lies beyond the horizon.

The enduring fascination with Hy-Brasil suggests that some mysteries transcend their historical contexts to become permanent features of human imagination. As we continue to explore our planet’s remaining mysteries, the legend of the mythical Irish island Brazil serves as a reminder that the most compelling geographical discoveries often begin not with empirical observation, but with the courageous act of believing that somewhere, beyond the mist and waves, extraordinary worlds await discovery.