Imagine standing beneath a sky that tells the story of creation, fall, and redemption-painted not by the hand of God, but by a man who, by the end of his ordeal, swore he was “no painter.” The Sistine Chapel is more than just a room in the Vatican; it is a crucible of artistic innovation, a theatre of faith, and a monument to the Renaissance’s boundless ambition. Whether you’re an art lover, a history buff, or a curious traveller Googling “visit Sistine Chapel,” this is your essential guide to one of humanity’s greatest achievements.

The origins and purpose of the Sistine Chapel

The Sistine Chapel, or Cappella Sistina, owes its name and existence to Pope Sixtus IV, who, between 1473 and 1481, decided the crumbling remains of an earlier chapel simply wouldn’t do for the papal court’s needs. The new chapel was built atop the old foundations, its asymmetrical plan a nod to the site’s history. The first mass was celebrated on 15 August 1483, marking its official debut as the spiritual heart of the Vatican.

Why was it built?

- To serve as the papal chapel for religious ceremonies.

- As the site of the papal conclave, where cardinals gather to elect a new pope-a tradition that continues to this day, complete with the iconic white or black smoke signals.

- As a display of papal prestige and a canvas for the greatest artists of the age.

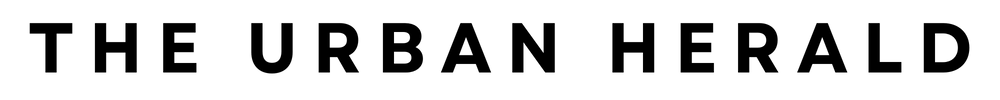

Architectural features and early decoration

From the outside, the Sistine Chapel is a study in Renaissance understatement-no grand entrance or flamboyant façade. Inside, however, it’s a different story. The chapel measures approximately 35 metres (118 feet) long, 14 metres (46 feet) wide, and 20 metres (66 feet) high. Its marble floor is inlaid with intricate Cosmati mosaics, and a marble screen divides the space into two unequal parts, reflecting its dual function for clergy and laity.

Early Decoration:

- The walls were originally adorned with frescoes by a veritable Renaissance all-star team: Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Pietro Perugino, and Cosimo Rosselli, among others.

- Two narrative cycles-The Life of Moses and The Life of Christ-run along the central tier of the walls, complemented by portraits of popes above.

- The ceiling? Originally a simple blue sky dotted with gold stars-hardly a hint of the drama to come.

Michelangelo’s ceiling: The genesis of genius

The commission and the challenge

In 1508, Pope Julius II, never one to think small, commissioned Michelangelo Buonarroti-already famous as a sculptor but a reluctant painter-to transform the chapel’s ceiling. Over four gruelling years (1508–1512), Michelangelo created what would become the most famous ceiling in the world, featuring over 300 figures in a visual symphony of biblical narrative, human anatomy, and divine drama.

The creation cycle

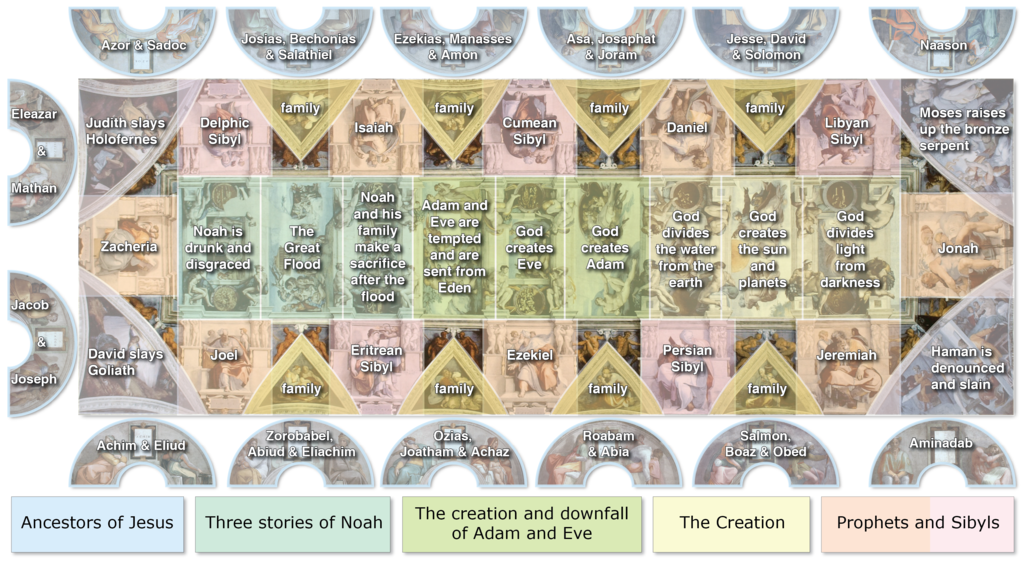

At the heart of the ceiling are nine central panels depicting stories from the Book of Genesis:

- The Separation of Light from Darkness

- The Creation of the Sun, Moon, and Plants

- The Separation of Land from Water

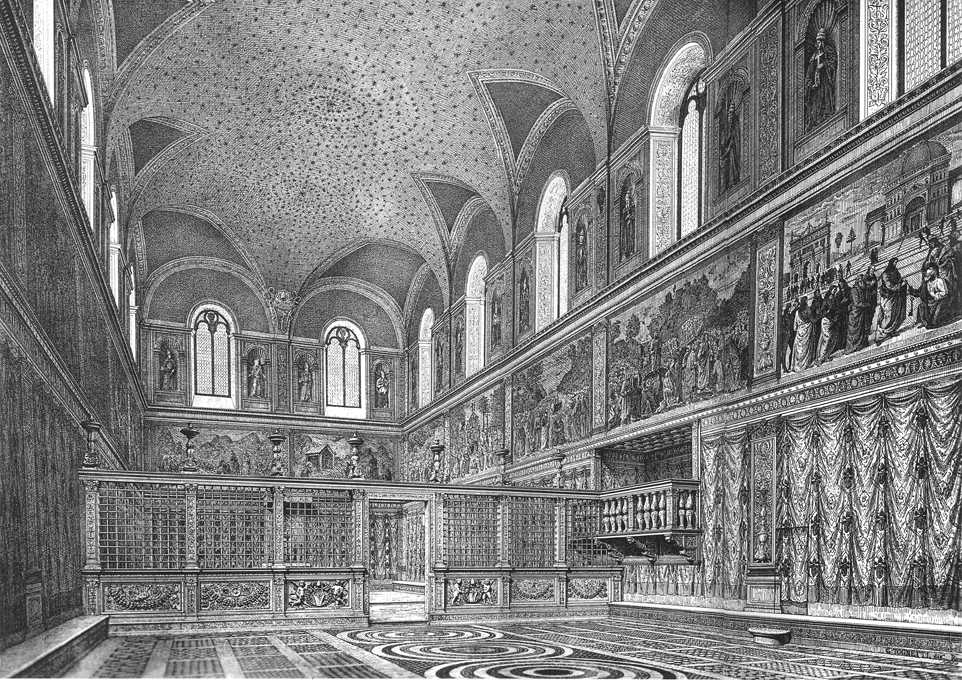

- The Creation of Adam (the iconic image of God reaching out to Adam)

- The Creation of Eve

- The Temptations of Christ

- The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden

- The Sacrifice of Noah

- The Great Flood

- The Drunkenness of Noah

Each scene is packed with symbolism. For example, The Creation of Adam is not just a moment of divine spark, but a meditation on human potential, dignity, and frailty-a touch that has become shorthand for the very act of creation.

The Deluge

The Deluge panel, depicting the Flood, is a tour de force of human emotion-fear, hope, despair-rendered in swirling forms and dramatic gestures. Here, Michelangelo’s mastery of anatomy and movement is on full display, as bodies twist and strain against the elements.

The Prophets and Sibyls

Surrounding the central scenes are twelve monumental figures: seven Old Testament prophets and five sibyls (female seers from classical antiquity). Their inclusion signals the universality of the Christian message-prophecy and revelation are not the monopoly of any one culture.

- Prophets: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, Joel, Zechariah, Jonah

- Sibyls: Delphic, Cumaean, Libyan, Persian, Erythraean

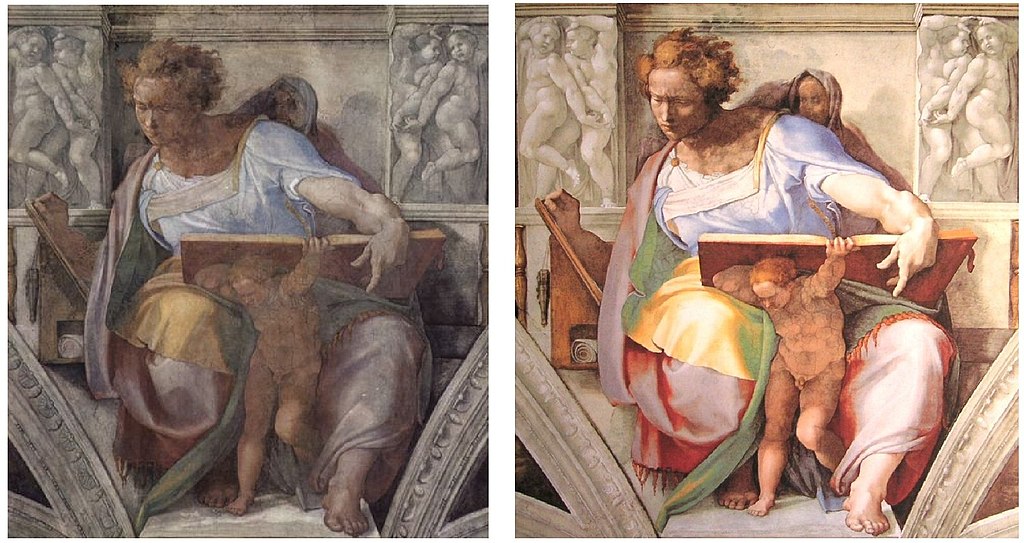

These figures, perched on thrones, are depicted in various states of contemplation, reading scrolls, or gesturing dramatically. The muscular forms-sometimes more robust than strictly necessary-reflect Michelangelo’s sculptor’s eye and perhaps his personal aesthetic preferences.

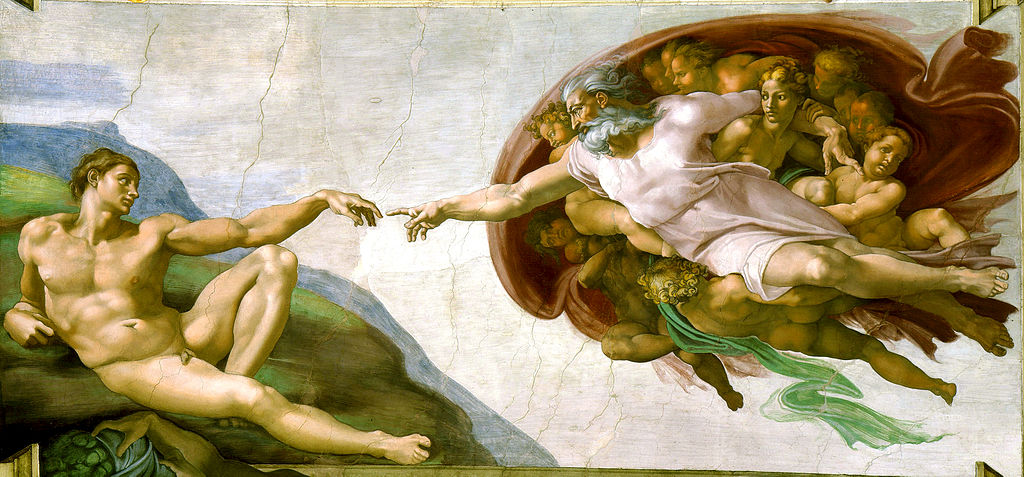

The Last Judgment: Michelangelo’s apocalyptic vision

Twenty years after completing the ceiling, Michelangelo returned to the Sistine Chapel to paint The Last Judgment (1536–1541) on the altar wall. This colossal fresco, teeming with more than 300 figures, depicts Christ’s Second Coming and the final sorting of souls.

Key Features:

- Christ, at the centre, is an imposing, almost wrathful figure-far from the gentle shepherd of earlier art.

- The saved ascend to heaven on the left; the damned are dragged to hell on the right.

- Saints, martyrs, and angels swirl in a cosmic vortex, their bodies rendered with unflinching anatomical precision.

Controversies:

- The nudity of many figures scandalised some contemporaries, leading to the later addition of strategically placed draperies (the so-called “fig-leaf campaign”).

- The fresco’s emotional intensity and ambiguous theology sparked debate-was Michelangelo’s vision too bleak, too humanist, too daring?

Yet, The Last Judgment remains a powerful meditation on justice, mercy, and the mystery of salvation.

Artistic techniques and materials: The alchemy of fresco

The fresco technique

Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling using buon fresco-a painstaking method where pigments are applied to wet lime plaster, chemically bonding as the plaster dries. Here’s how it works:

- Preparation: The ceiling was first stripped of its earlier starry sky fresco. A rough layer of plaster (arriccio) was applied, followed by a smooth, fine layer (intonaco) for each day’s work.

- Cartoons and Pouncing: Full-size drawings (cartoons) were pricked with pinholes and dusted with charcoal to transfer the design onto the wet plaster.

- Painting: Only as much plaster as could be painted in a day (giornata) was applied, demanding speed and precision. Mistakes? Start over-no pressure.

- Pigments: Michelangelo used a limited palette of earth tones-ochres, sienna, carbon black, terre verte-and precious lapis lazuli for blue. The chemistry of the plaster ensured durability, with the pigment encased in calcium carbonate as the plaster cured.

Working conditions

Forget the Hollywood myth of Michelangelo painting while lying on his back. He worked standing, craning his neck upwards for hours on end, perched on custom-designed scaffolding that left the chapel’s floor free for ongoing ceremonies. The physical toll was immense-he complained of goiters, back pain, and a permanently upturned beard.

He was assisted by a small team for the more minor details, but the vision and execution were overwhelmingly his own.

Symbolism and interpretation: Layers of meaning

The Sistine Chapel is a visual catechism-a narrative of creation, fall, and redemption, told in pigment and plaster.

- Biblical References: The central panels depict Genesis, but the surrounding figures and scenes expand the story to encompass prophecy, salvation history, and the universality of God’s promise.

- Theological Themes: The ceiling is a meditation on humanity’s need for salvation, the covenant between God and man, and the hope of redemption through Christ.

- Renaissance Humanism: Michelangelo’s figures are not ethereal spirits but robust, dynamic humans-muscular, flawed, striving. This reflects the Renaissance celebration of the human body and intellect, as well as the artist’s own fascination with anatomy and movement.

- Hidden Meanings: Scholars continue to debate the presence of “concealed” or “forbidden” messages-perhaps a testament to the work’s inexhaustible richness.

The Sistine Chapel today: Visiting, conservation, and legacy

Visiting the Sistine Chapel

The Sistine Chapel remains one of the most visited sites in the world, drawing millions of pilgrims, art lovers, and tourists each year. Here’s what you need to know:

- Location: Within the Vatican Museums, Vatican City.

- Opening Hours: Typically open Monday to Saturday, 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM (last entry at 4:00 PM), but check the Vatican Museums’ official site for updates.

- Tickets: Advance booking is highly recommended, especially in peak season. Tickets can be purchased online.

- Dress Code: Modest attire is required-shoulders and knees must be covered.

- Photography: Strictly prohibited inside the chapel.

Disclosure: This post contains affiliate links that help support and maintain this website. If you click through and make a purchase, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you.

Conservation efforts

Centuries of candle smoke, dust, and humidity had dulled Michelangelo’s colours. A major restoration (1980–1994) revealed the original brilliance of the frescoes, sparking both awe and debate about the ethics of restoration. Ongoing conservation is a constant challenge, balancing public access with the need to preserve this fragile masterpiece for future generations.

Ongoing significance

The Sistine Chapel is not a museum piece but a living space-still used for papal ceremonies, conclaves, and as a symbol of the Vatican’s spiritual and cultural heritage. Its impact on art, theology, and popular culture is immeasurable, inspiring generations of artists and thinkers.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Sistine Chapel famous for?

Its ceiling and altar wall frescoes by Michelangelo, particularly The Creation of Adam and The Last Judgment.

Who commissioned the Sistine Chapel?

Pope Sixtus IV commissioned the building; Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo’s ceiling.

How long did it take Michelangelo to paint the ceiling?

Four years, from 1508 to 1512.

Can you visit the Sistine Chapel?

Yes, as part of the Vatican Museums. Advance tickets and modest dress are required.

What is the meaning of the figures in the Sistine Chapel ceiling?

They represent biblical stories, prophets, and sibyls, symbolising humanity’s journey from creation to redemption.

Final Thoughts

The Sistine Chapel is not just a room, nor merely a collection of paintings. It is a testament to the heights of human creativity and the depths of spiritual longing-a place where art, faith, and history converge beneath a painted sky. Whether you’re planning your own pilgrimage or simply marvelling from afar, the Sistine Chapel remains, in every sense, a wonder of the world.